We all know the old adage “you can never trust the network”. When working with distributed systems you learn this very quickly. Networks requests will fail. Instead of building “fault-free” software, it is much more pragmatic and smarter to build fault-resistant software. Software which anticipates faults and handles them accordingly.

Some time ago I was fascinated with the idea of event sourcing, building a model from a log of events and never modifying your events, only appending new ones. Kind of like a bank-ledger. You don’t set and modify a balance, you either add an income event or add an expense event. It’s an “append-only” system.

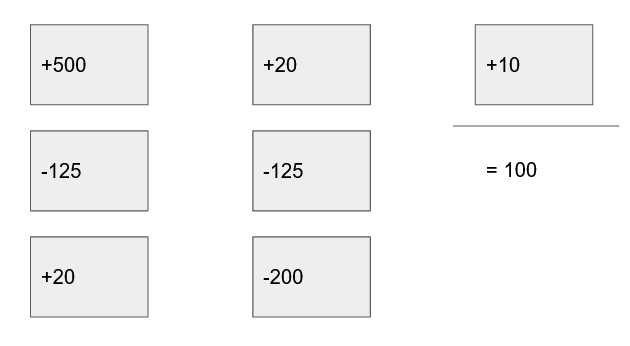

We have a log of events, and these are all sorted by time and have their own ID (optionally some kind of hash). From those events we use a deterministic algorithm to build a model. In the bank account analogy the model would be “our account balance is the sum of all income and expense events”.

The above example shows a log of incomes and expenses that end up in an account balance of 100.

Event sourcing has some neat properties and advantages I was curious about.

- Trivial to share state within a network of peers

- Everyone just occasionally shares their events with each other and re-evaluates their model

- No modification of data

- Spreading events over a network (with other peers as middlemen) is trivial

- Just make sure to share both your own events, and those of your peers

- Understanding why the system acts a certain way at timepoint

Tis simple, just check what events were available at that time. - If we implement a feature in our model in the future, we can apply it to previous events and immediately get the benefits.

As always, there are some significant drawbacks.

- Append-only really does mean no modification. Make sure you never add personally identifiable information to events.

- Remember that IP addresses can in some cases be regarded as PII

- Events have to be stored forever. Altough you can technically create a snapshot event this introduces a risk. How to verify correctness of the snapshot?

- How do we handle versioning of events? It requires a great deal of faith in ones ability to think that ALL events you ever create will anticipate every future use-case.

To sum up event sourcing, cool idea in theory. But probably kinda hard in practice. So how do you know when to use event sourcing in practice? Well, you try it out!

Project: MailFiles Link to heading

Enter the project MailFiles. A peer-to-peer network where files can be sent between each other. This is a project I created to learn more about the how event sourcing works in practice. The idea is dead simple. Use event sourcing as the base for spreading knowledge of the network structure. Then share files within that network.

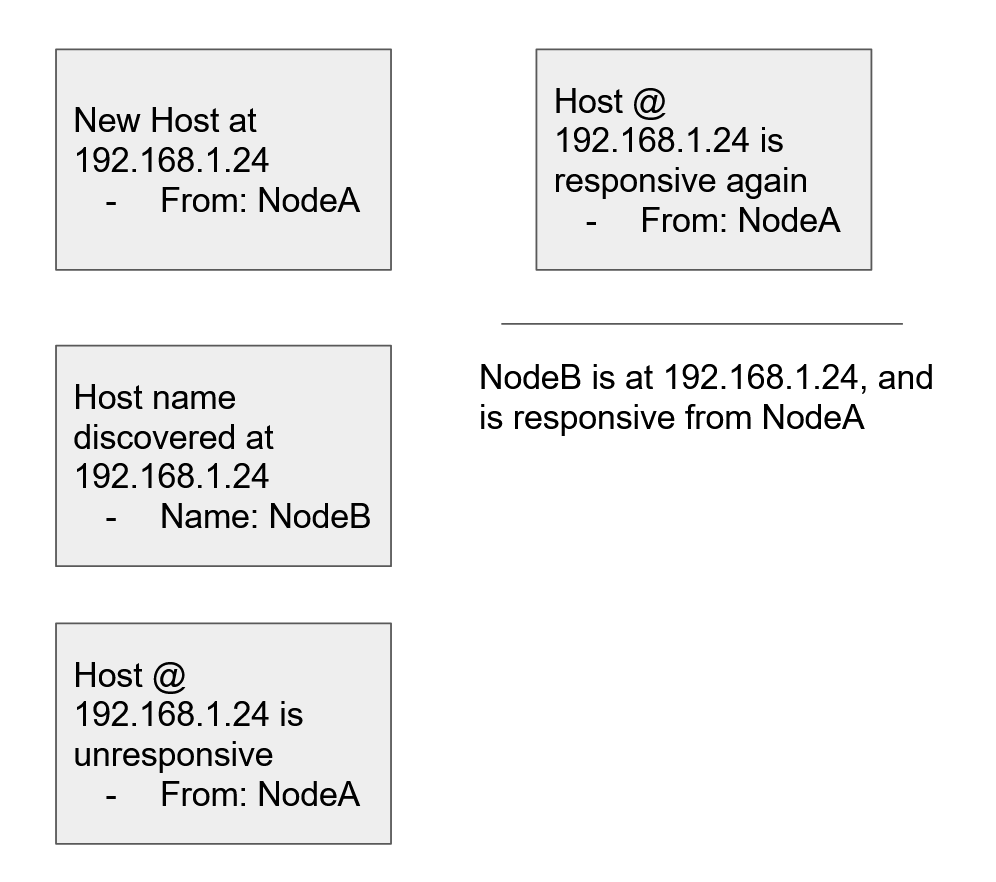

Finding hosts within that network consists of generating local knowledge and spreading knowledge. Local knowledge comes from a configuration file. A configuration file like the one below would generate a config event, representing a new configuration.

{

"Id": "NodeA",

"Host": "192.168.1.20",

"DisplayName": "Node A"

}

Initially this information would sit with the node where the configuration is available at, but after knowledge is spread (called “gossiping”) the information will become available to other nodes. The configuration creates a connection between two nodes, and they will start gossiping with each other.

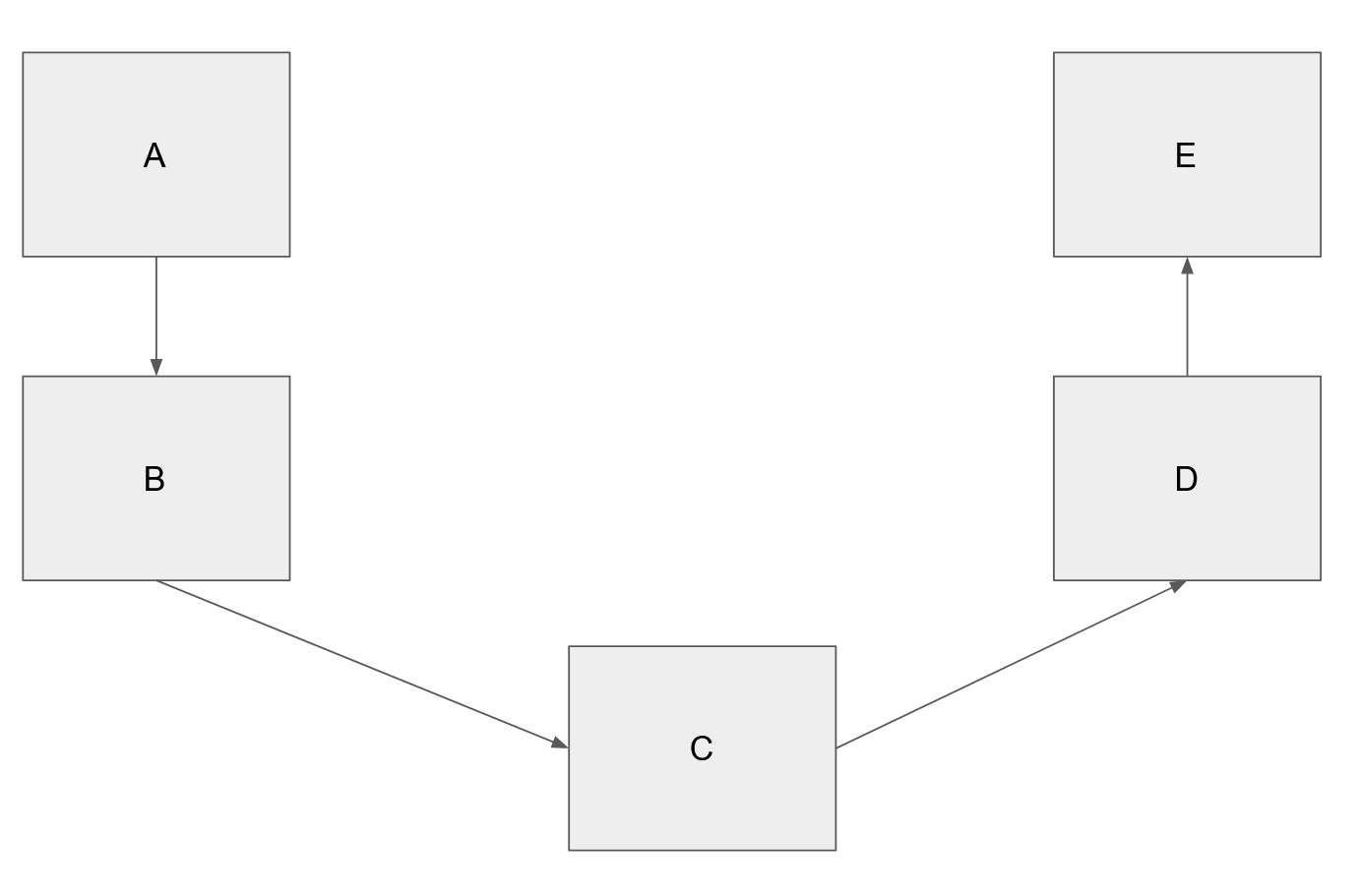

If A and B are connected, then A will talk to B. If B is also connected to C, then they will gossip as well. Once B talks to A again, B will bring news of C to A. This process is called Host Discovery.

Again gossiping is very simple. One node connects to another node and says “these are my events, what are yours?”. This is the protobuf definition I used for MailFiles:

/// Service for discovering the network

service Discovery {

/// Returns a fingerprint of the current network model.

rpc Fingerprint (FingerprintRequest) returns (FingerprintReply);

/// Allows a client to push all their events to this service,

/// and read all events from the service.

rpc Gossip (GossipRequest) returns (GossipReply);

}

// AUTHORS NOTE: Yes, I know `Gossip` should be streamed but this is

// a project focused on learning.

As more and more hosts are found, each node increases it’s reach for what servers it can send files to. Since each node gets a copy of the network topology, it can simply create a path through the network and say “send this file A –> B –> C –> D –> E” to send files to a distant host.

If the network topology changes by nodes going offline, the original node can resend the file using a different path through the network. If the nodes comes back online, the network will eventually gossip about this and the original node will know it can resend through the same nodes. In that sense, the network is regenerative.

Conclusions Link to heading

Event sourcing can be a powerful tool. Like any tool it should be used thoughtfully, after MailFiles I genuinely think that event sourcing is a great tool for modeling advanced peer-to-peer networks, since it requires very little code to implement.

With surprisingly little effort it provides a fault-resiliant protocol, while also being somewhat easy to grasp.